Anyone working with patents has noticed: Artificial Intelligence is no longer just a conference topic – it has become a practical tool. From New York to Brasilia, patent Examiners are experimenting with semantic searches, IP firms are redesigning prospecting routines and office action responses, and Applicants are demanding speed, cost-efficiency, and predictability. The key insight, however, is not simply to “replace humans.” Rather, it is to industrialize stages – through AI – without abandoning technical review and accountability.

What the authorities are actually doing:

▪ USPTO (USA): Integrated Similarity Search (SimSearch) into its search environment (PE2E), allowing prior art to be ranked based on similarity to the patent application text. A pilot program, ASAP! (Automated Search Pilot), now provides an AI-generated “lightning packet” of references shortly after filing. Additionally, dynamic re-execution after amendments updates the ranked references automatically as claims or specifications change. The AI also uses IPC/CPC and application content to search internal and public databases, expanding prior art coverage. Expected outcome: Enhanced quality at the initial filing and amendment stages, reducing back-and-forth during substantive examination.

▪ EPO (Europe): Uses AI for automatic pre-classification and reclassification, leveling the starting point, and for AI-assisted search/screening through semantic similarity kNN (K-nearest neighbor search) for initial shortlists. Its Patent Translate (EPO + Google) neural translation tool enables multicorpus search. Technical entities are extracted by AI, allowing automatic annotation (e.g. numbers, compounds, parameters), which accelerates evidence-driven reading. In practice: Examiners begin with a “vector map” of the dataset, not a blank page.

▪ JPO (Japan): Is expanding internal expertise in AI-assisted examination and harmonizing practices within the IP5 NET/AI framework. Focus: Consistency and response time.

▪ CNIPA (China): Is investing in intelligent search and examination systems using image recognition, instant translation, and semantic comparison – valuable for patents, utility models, and especially industrial designs. AI highlights relevant references for Examiners and detects dossier inconsistencies (e.g. missing attachments) via formal deficiency modules.

▪ INPI (Brazil): Has been progressing pragmatically, discussing AI-specific examination guidelines and signaling the use of AI assistance in search and screening, collaborating with WIPO, academia, and industry to enhance searches in key fields such as chemistry, pharmaceuticals, and industrial designs. For IP firms and Applicants, the message is clear: AI will support dossier quality – not outsource substantive examination.

Common thread across all five authorities: AI as a co-pilot, with traceability (logs) and transparency, preserving human decisions and due process – focused on speed, coverage, and consistency.

Where AI is reshaping patent practitioners’ routines:

Table 1 – Core tasks, typical AI techniques, and practical effects across patent departments

Tools appearing in daily practice:

- Similarity Search (SimSearch) (USPTO): Textual similarity for prior art in PE2E search.

- Patent Translate (EPO + Google): Patent-specific neural translation.

- CNIPA’s AI modules: Patent Search and Analysis System (PSS) with translation, similarity, chemical structure search, and stats, covering over 100 jurisdictions, including industrial design data. i-Search, for search and examination workflows.

- Corporate legal support solutions: For instance, Legal and Cognitio (data/deadline governance).

- DeepL Agent: Corporate AI agent that handles translation, review, data collection, and publication within enterprise systems, with a focus on security, terminology customization, and DeepL integration.

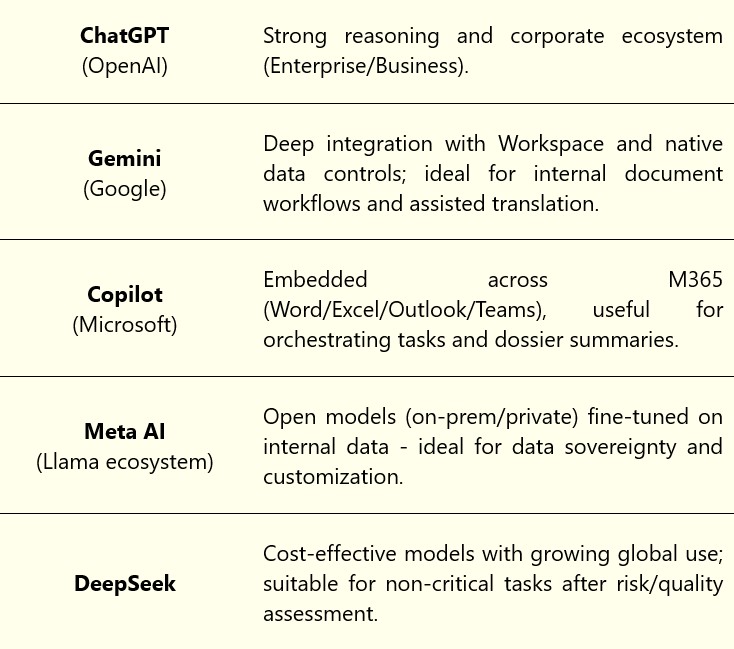

- Top 5 LLMs for Patent context:

Table 2 – Top 5 LLMs for Patents

Practical tip: For sensitive tasks (e.g. claims, experimental data), prioritize corporate plans or private deployments (zero retention, audit trails, SSO, DPAs), and establish a clear positive-use list (screening, drafting, analytics) versus red-flagged uses (automated decisions, uncontracted data submission).

Unfiltered advantages:

– Real speed: Shortlists in minutes, not hours.

– Broader coverage: More languages and formats (text, image, formulae, structures).

– Consistency: Standardized classification/screening raises the quality baseline.

– Quality at filing: With “early” prior art packets, the first office action tends to address merits, not basic deficiencies.

Barriers (and how to avoid them):

◦ Hallucination and overconfidence: Generalist models may fabricate sources. Use specialized legal/technical engines and double-check.

◦ Confidentiality and compliance: Do not upload experimental/draft notebooks to services lacking corporate contracts and clear policies.

◦ Disclosure (enablement) in AI inventions: Clearly explain how the model achieves the technical effect (data, training, metrics); saying “I applied AI” is insufficient.

◦ Prompt quality and governance: Without internal standards (prompts, checklists, logs), traceability and value diminish.

Five examples of grounded use cases:

- Chemistry – Prior art pre-screening: Abstract + claims → similarity engine + IPC/CPC filters → neural translation for CN/JP sources. Output: Annotated shortlist + code-based heatmap.

- FTO for packaging and industrial designs: Image search (icons, graphics, layouts) + textual similarity in design claims. Output: Visual element risk matrix.

- Response to inventive step office actions: AI drafts the problem-solution logic with term-by-term comparisons; team adds technical effects and data. Output: Draft with solid technical narrative.

- Portfolio analytics for M&A: Embedding-based clustering + citation panel reveals “hidden gems” and gaps. Output: Visual due diligence report.

- Verification of cited jurisprudence: Legal AI checks administrative/judicial references, numbering, and content, and updates precedents; technical analyst focuses on patentability reasoning. Output: Brief with verified citations.

Chart 1 – Where AI Fits in the Patent Lifecycle

Quick takeaway: Greatest gains are seen in areas involving volume (search/screening) and languages (translation). In substantive examination, AI prepares the ground; the revision and decision remain human.

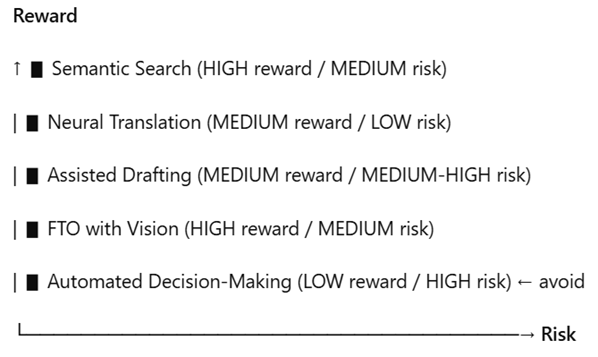

Chart 2 – Risk x Reward Matrix

Quick takeaway: Prioritize search/translation/screening; treat “drafting” as assistance, not as autopilot; automated decision-making, not at all.

Brazil, here and now:

. Patent practitioners working in chemistry/pharmaceuticals/agriculture are realizing immediate benefits by combining semantic search with computer vision for figures/structures and neural translation.

. Industrial Design represents fertile ground for image-based search and systematic collection of dated evidence.

. In patent applications involving AI as the subject matter of the invention, describe the data, training, metrics, and technical effects – this reduces objections and facilitates the Examiner’s task.

. Governance (privacy, confidentiality, audit trails) is already a competitive differentiator in Brazil – enterprise clients demand it.

Closing:

Artificial Intelligence in patents is no longer a question of if, but of where and how to deploy it. The patent practitioners that treat AI as infrastructure – anchored in clear processes, contractual safeguards, measurable quality metrics, and rigorous human review – deliver faster, error less, and achieve more predictable outcomes. The mandate for 2025 is practical: industrialize search, screening, and translation; use drafting assistance with accountability; and keep automated decision-making off-limits. In Brazil and worldwide, the opportunity remains open – press the button, with discretion.